Essay by Neil Johnson

Who gives himself or herself a birthday gift of a visit to a friend? I did. That was the power of Clyde Connell.

Clyde was a woman of inspiration to many artists in northwest Louisiana. Named after Scotland’s River Clyde and raised on a plantation just north of Shreveport, she only left this neck of the woods to travel to New York City and other places for the Presbyterian Church and for art. She always returned to evolve her own art and eventually became a homegrown, internationally celebrated, truly original artist.

I had heard of her, but I don’t remember meeting her until I was assigned to photograph her as my first post-grad professional magazine photojournalism assignment for the newborn Louisiana Life. That 1981 assignment turned into more than a decade of 40-minute drives out to the Spanish moss-laden cypress trees on the west bank of Lake Bistineau. Having spent my high school and college summers water-skiing down its channels, I always thought of Bistineau as a place for fun escape with my ski-pals. As an adult, the lake took on new meaning as my Clyde Connell destination.

Clyde’s home-studio became, over the years, a place of inspiration for a hundred other artists, gallery curators, documentary videographers, art-lover celebrities like Lily Tomlin and even legendary photographer Mary Ellen Mark. In her later years, Clyde did not have to travel to see the world. The world traveled to see her.

Photography introduced me to Clyde and, after our friendship progressed, photography remained ever present, as it was an important avenue for her art to gain entrance to galleries and publications. Of course, I was not the only photographer who pointed a camera at her or her work, but I took it as a personal duty—and pleasure—to be regular with my medium. I don't remember ever not pulling out my camera bag while out there.

But Clyde and her work were not simply photographic subjects for me. She was about spiritual and intellectual and artistic inspiration. To be in her humble home was like meditation. Clyde, her environment, her life and her work were one. She lived her art, which was intensely about and from her immediate rural Louisiana environment combined with her worldview, which went far afield and included many social issues, especially women’s.

The best artists come about their work honestly and on their own, without people pushing them in any direction. No one but her own muse sent her down a new, quiet and interesting path, which combined a strong connection to the earth with a love for the deep mysteries of what makes us human. Her techniques and style were her own inventions. She set out to find herself and explore her world and did so intuitively and intrinsically in an creative and prolific career that began well into the second half of her long life. She lived to be 97 and did not stop making art until just before her death in 1998.

Several times, when my birthday included a chunk of unscheduled time on a weekday, I would purposely give myself the gift of driving out to Clyde’s to just sit, visit and soak in the atmosphere. These remain several of my favorite birthdays in my memory. We would sit with her in her studio and discuss current world events. On warm days with the AC window unit buzzing, she would enjoy her rocking chair, and on cold days, she would be bundled in a blanket in her easy chair. She was not an “old woman” to me. She was a woman of energy and ideas and intelligence and grace.

Many times I moved furniture out of the way in her small sitting room or dining room to transform them into studio space. I documented her sculpture and paintings for more than a decade and was honored to create the images for her Paris exhibit catalog.

To prepare for this essay, I went through my whole collection of Clyde portraits and had forgotten how many times she posed for me or allowed me to photograph her while she worked. My camera liked her. Into her nineties, she retained a special beauty—a beauty that was in her and gathered around her.

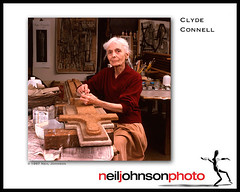

In searching for just the right Clyde image, I kept coming back to this one, my favorite. She is in her studio working on what I consider to be her most powerful series of sculptures, her “bound women” series. These women are bound and blinded by fabric—fabric made up of misogyny and sexism and many other things that take away a person’s freedom. When I made this photo, Clyde was unbound. She was a free woman. Freed by her art.

Again, photography is a time machine. In this case, it whisks me back to the 1980s, back to the shore of Lake Bistineau. To Clyde.

Neil Johnson

August 1, 2013

www.njphoto.com

Friday, August 2, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)