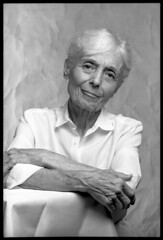

Suffering is not immediately apparent in the story of artist Clyde Connell.

The trials of her life were hidden because the artist did not want the public to know about her misfortunes. The code of her proud planter family, the Dixons, was to hold one's head high despite difficulties.

The childhood enjoyed by the nine Dixon siblings was one of privilege. Clyde was raised largely by African-American women who were Dixon housekeepers. The two-story house in Belcher was the center of a farming business that encompassed 5 plantations. Clyde attended Brenau College, Georgia, and briefly attended Vanderbilt University, Tennessee.

She married Thomas Dixon Connell, son of a planter in Belcher, in 1922. Shortly thereafter her father, the handsome Jim Dixon, died. He shot himself while cleaning his gun.

Management of the Dixon business was taken over by Clyde's husband. Over the next several decades, the difficult years of the Great Depression, the family land was steadily lost to foreclosures. By the end of WWII the family had only the big house and 5 acres of land.

In 1949 her husband, known as TD, won the position of superintendent of the Caddo Parish Penal Farm. At the farm Clyde developed a studio in what had been a milk shed. She raised 3 children and frequently took over the care of nephews and nieces during the summer months.

But TD was ousted from the his job at the Penal farm in 1959, two years short of retirement. The children had been raised; they were independent. Clyde and TD, short of resources, chose to move to a cabin on Lake Bistineau.

There was no room for storage of Clyde's family heirlooms, art or records from her years of volunteer work in the Southern Presbyterian Church. Clyde destroyed much of the material.

In Shreveport the abstract art exhibited by Clyde and her cohorts was seen by the public as incomprehensible and probably anti-American. The Dixon family was not particularly supportive of her art making.

For 3 years Clyde walked the land at the edge of Lake Bistineau and thought about her life and art. Her volunteer work with the Presbyterian Church had brought her to New York City for many meetings. It was in Manhattan that she had developed a mind for the creation and the business of art. Her goal was to do as William Faulkner had done; make successful art using the local environment. Yet her isolation and lack of financial resources hampered her growth.

Clyde wanted to fabricate a series of designs she called Sun Paths in sheet metal. She did not have the money to do so. When she was given a large gift of paper, she went to work in collage and in drawings on paper.

Wood and paper, the most basic and affordable of materials, became her mainstays. She developed a papier mache coating for her sculptures that gave her work a stone-like skin.

In the meantime, she lost her eldest son, Dixon, to an untimely death. To say that her husband was supportive of her work in art would not be true.

Though she was in her 70's Clyde had the fortitude of an ingenue. She nailed, glued, coated and painted a stream of work. Her sculpture grew increasingly larger and more demanding of attention. But she entered few shows. She lacked the funds to ship her work to distant venues.

Her breakthrough came via Texas. She sent slides of her work to Murray Smithers at the Delahunty Gallery, Dallas. When he visited her at Lake Bistineau he added Clyde to his roster. Clyde began to sell art in Dallas and in Houston. By 1981 the Delahunty connection won Clyde a show at the Clocktower Gallery, a cutting edge Manhattan venue. The reviewer of the New York Times was impressed.

People from Shreveport who saw her work in NYC began to collect work by Clyde.

Clyde had long made a point of her sympathy for the plight of her black neighbors. She enjoyed the singing and appreciated the aspirations she saw in the black community. Her work for the Southern Presbyterian church was teaching the young in rural black churches. At the penal farm she spent much time making portraits of the prisoners, most of whom were black.

In the 1950's and 1960's her family was not comfortable with her work in black churches; it amounted to participation in the civil rights movement. But by the 1980's she began to tell interviewers that the background of her Swamp Songs included the sounds of violence, death and mourning in the black community. She explained that her appreciation of black struggle was an emotional reservoir from which she drew much of her imagery.

The Non-persons and Bound People series came forth in the 1980's. Clyde told interviewers that her new sculptures were about women and the social inhibitions that limited their activities.

Only a small circle of family and friends realized how much the suffering portrayed in her art figures related directly to the life of the artist herself.

Robert Trudeau

Thanks to my numerous sources for this series of articles on the life of Clyde Connell:

Martha Dunphy, frequent companion of Clyde's in her travels from the 70's to the 90's.

Jerry Slack, Gator Group artist alongside Clyde.

Al Evans, collector.

Bryan Connell, son of the artist.

Clyde Ent, daughter of the artist.

Dixon Ent, grandson.

Carol Shafton, grand-daughter.

Bennett Sewell, great nephew.

Pat Sewell, great nephew.

Talbot Hopkins, great niece.

Charlotte Moser's book, Clyde Connell, the Life and Art of a Louisiana Woman.

Meadows Museum of Art's "Clyde Connell, Daughter of the Bayou" Catalog.

John Fredericks, construction assistant to Clyde for some 20 years.

"Swamp Song," a film about Clyde by Adam Simon.

Obituary and reviews in the New York Times.

Monday, September 15, 2008

Sunday, September 14, 2008

Enjoy the party at Artspace on Fri, Sept 19, 7 to 10 pm, in honor of Clyde Connell

Clyde Connell's peers in the history of Louisiana art are luminaries Clementine Hunter and George Rodrigues.

Like the untutored Natchitoches artist Clementine Hunter, the North Louisiana artist Clyde Connell was female and largely self-taught.

Clyde was born on the Dixon Plantation, Belcher, in 1901. Her life as a woman of the planter class included basic art lessons. It was during her trips to NYC as a Presbyterian education volunteer that she visited and re-visited the Museum of Modern Art and other museums and galleries. She developed her persuasive skill and vision between NYC and Shreveport, where she worked in a studio alongside artist friends in the 1970's.

Like the artist George Rodrigues, Clyde used Louisiana material in winning national attention. The wood, paper, metal, rocks and rattan used by Clyde in her sculpture reflected the colors and shapes in the landscape of Lake Bistineau, Clyde's home from the 1960's until her death in 1998.

In the 1980's Clyde fulfilled her goal of winning the art world's highest accolades - exhibiting in Manhattan and Paris, in Los Angeles and Mexico City, in Houston and New Orleans. Her work was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other prestigious museums.

Clyde's fame arrived when she was in her 80's. In the previous decades she had raised 3 children and created hundreds of paintings, woodcuts and sculptures. Her inspiration came from artists such as William Faulkner, whose national acclaim as a novelist was based on novels about the people of Mississippi.

Hope to see you at Artspace on Friday night. In addition to the art and people, you'll enjoy singer Kenny Bill Stinson, a Louisiana musical artist in his own right.

Please see images from the party at flickr.com/robert_trudeau.

Like the untutored Natchitoches artist Clementine Hunter, the North Louisiana artist Clyde Connell was female and largely self-taught.

Clyde was born on the Dixon Plantation, Belcher, in 1901. Her life as a woman of the planter class included basic art lessons. It was during her trips to NYC as a Presbyterian education volunteer that she visited and re-visited the Museum of Modern Art and other museums and galleries. She developed her persuasive skill and vision between NYC and Shreveport, where she worked in a studio alongside artist friends in the 1970's.

Like the artist George Rodrigues, Clyde used Louisiana material in winning national attention. The wood, paper, metal, rocks and rattan used by Clyde in her sculpture reflected the colors and shapes in the landscape of Lake Bistineau, Clyde's home from the 1960's until her death in 1998.

In the 1980's Clyde fulfilled her goal of winning the art world's highest accolades - exhibiting in Manhattan and Paris, in Los Angeles and Mexico City, in Houston and New Orleans. Her work was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other prestigious museums.

Clyde's fame arrived when she was in her 80's. In the previous decades she had raised 3 children and created hundreds of paintings, woodcuts and sculptures. Her inspiration came from artists such as William Faulkner, whose national acclaim as a novelist was based on novels about the people of Mississippi.

Hope to see you at Artspace on Friday night. In addition to the art and people, you'll enjoy singer Kenny Bill Stinson, a Louisiana musical artist in his own right.

Please see images from the party at flickr.com/robert_trudeau.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)